What is functional neural circuitry underlying motivated behaviors?

|

My master's research involved a variety of behavioral projects looking at the relationship between stress and the intake of high-fat, high-sugar palatable foods. I hypothesized that stress would increase consumption of palatable food, and that a history of access to palatable food would attenuate anxiety-like behavior on the elevated plus maze. Contrary to my hypothesis, I found that subjects exposed to acute and chronic restraint stress (but not footshock stress) had reduced intake of palatable food compared to non-stressed controls, and that a history of chronic restraint stress (but not a history of palatable food access) attenuated anxiety-like behavior on the elevated plus maze compared to non-stressed controls.

|

|

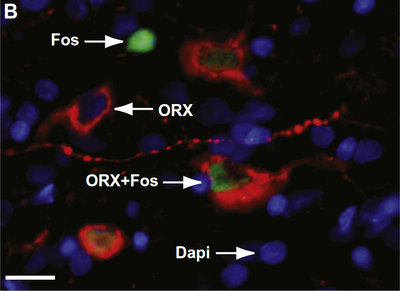

After my master's, my research shifted to projects further characterizing the behavioral paradigm of learned cue-induced feeding. In this preparation, a learned cue for food can drive overeating even in sated subjects. Using this paradigm, I then identified the selective recruitment of orexin/hypocretin, but not melanin-concentrating hormone, neurons by a learned food-cue in the absence of hunger, food presentation, or consumption. A follow-up study, led by Dr. Sindy Cole, found that selective recruitment of this population of neurons develops over the course of appetitive Pavlovian conditioning. Together, this work demonstrated that orexin/hypocretin neurons become engaged during food-cue learning and could later be reactivated by these cues to potentially regulate feeding behavior.

|

|

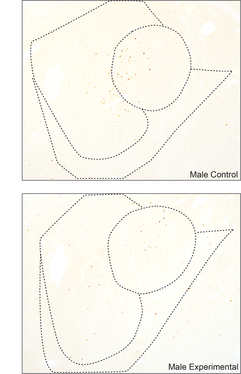

I also completed a series of projects focused on sex differences in learned fear cue-inhibited eating. I characterized behavioral models of fear-cue inhibited feeding and found sex differences in the ability of discrete and contextual cues to inhibit feeding despite food-deprivation . Specifically, females exhibited a more generalized and prolonged inhibition of feeding compared to males, even though there were no sex differences in the expression of freezing behavior (a commonly used measure of conditioned fear). Then, by mapping activation patterns of 23 distinct cell groups, I provided the first evidence of the forebrain-hindbrain network underlying fear-cue inhibited feeding. Interestingly, I found that the medial prefrontal cortex was sex-specifically recruited in females. These studies are especially relevant given the higher reported rates of anxiety and eating disorders in women compared to men, and offer an interesting avenue for future research regarding female susceptibility in co-morbid anxiety and eating disorders.

|

|

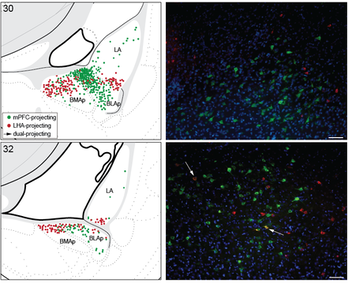

As part of my dissertation work I completed a detailed investigation into the organization of connections between the amygdala, medial prefrontal cortex, and lateral hypothalamus-- three regions hypothesized to be critical for the expression of cue-induced and cue-inhibited feeding. In describing multiple topographically organized pathways for amygdalar influence on the LHA via direct and mPFC routes, I provided the first evidence that these are parallel pathways that originate from different neurons. |

|

For my postdoctoral research, I continued to use systems neuroscience approaches to investigate the neural circuity underlying motivated behaviors and whether activation of that circuitry is similar between the sexes. However, I shifted from studying the motivation to eat to the motivation of juvenile subjects to engage in play behavior. In one series of projects, I investigated the roles of three neuropeptide systems: oxytocin, vasopressin, and orexin/hypocretin in the social play behavior. In a second series of projects, I investigated the importance of the mesocorticolimbic dopamine system in the regulation of social play.

|

|

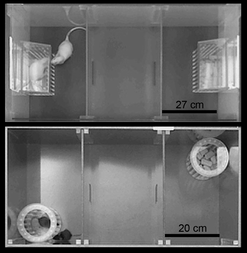

During my postdoc, I also characterized a behavioral paradigm that can be use to delineate the neural substrates that coordinate the expression of multiple motivated behaviors. Specifically, I investigated the competition between the choice to seek social interaction versus the choice to seek food, and assessed how this competition was modulated by internal cues (social isolation, food deprivation), external cues (stimulus salience, time-of-day), sex (males, females), age (adolescents, adults), and rodent model (Wistar rats, C57BL/6 mice). |